It is 1200 AD and China is a land divided. The Song empire has been driven south by the fierce Jurchen peoples, and now corrupt officials scramble to save their own hides while ordinary men and women struggle just to survive. Yet in the far north, under the eye of Genghis Khan, a young hero is rising whose destiny it is to change history… Trained in kung fu by the Seven Heroes themselves, Guo Jing will face betrayals, mythical villains and an enemy as cunning as he is ruthless. Filled with breathless action from the first page, and populated with unforgettable characters, A Hero Born is the first step in a journey beloved by millions of readers worldwide.

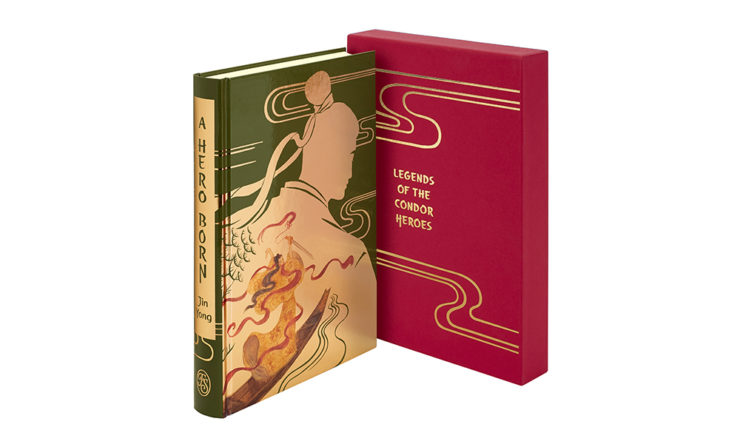

The Folio Society is bringing Jin Yong’s wuxia epic to life with color illustrations by artist Ye Luying. We’re excited to share some of the art below, along with the introduction by Ken Liu.

When introducing Jin Yong’s work to anglophone readers, marketers tend to rely on comparisons that will instantly give westerners a sense of Jin Yong’s popularity in the sinophone world. Thus, Jin Yong has been described as a ‘Chinese Tolkien’ and Legends of the Condor Heroes likened to Lord of the Rings. The analogy is helpful, up to a point – both authors, for instance, composed their grand visions of good vs evil after living through the devastation of worldwide war, and Jin Yong’s books ushered in a new era of wuxia (martial arts) fantasy much like Tolkien’s tomes inspired countless epic fantasies in their wake. Besides, how can I argue against the juxtaposition when in both Rings and Condor Heroes oversized raptors show up at convenient points in the plot like aerial Ubers to whisk our heroes to safety? It’s almost too perfect.

However, the Tolkien comparison risks setting up the wrong expectations. Whereas Middle-Earth is a separate realm with its own history, mythology, peoples, literatures, and languages (however much they may echo our own histories and cultures), Jin Yong’s fantastic jianghu, full of men and women endowed with superhuman abilities accomplishing feats that defy the laws of physics, paradoxically derives much of its strength by being rooted in the real history and culture of China. The poems sprinkled among its pages are real poems penned by real poets; the philosophies and religious texts that offer comfort and guidance to its heroes are real books that have influenced the author’s homeland; the suffering of the people and the atrocities committed by invaders and craven officials are based on historical facts.

Jin Yong’s historical re-imagination is sui generis. Much better then, in my opinion, to reset one’s expectations and meet Jin Yong and his world on their own terms.

Many detailed and scholarly biographies of Jin Yong exist, so I’ll give only a very cursory sketch here, relevant to the present work.

‘Jin Yong’ (金庸) is the pen name of 查良鏞 / Louis Cha Leungyung – it is in fact a decomposition of the last character in the author’s Chinese given name. The multiplicity of names in that last sentence, crossing scripts, languages (including varieties of Sinitic languages), and political borders, is a microcosm of the vicissitudes of the fate of many Chinese intellectuals of the twentieth century.

Born in 1924 in Haining, Zhejiang Province (the beauty of Wu Chinese, the language of the region, is a recurring theme in his novels), Jin Yong was descended from a prominent clan that produced many notable scholars and officials in the Ming and Qing dynasties. As a result of the family’s large collection of books, he read widely as a child, including classic wuxia tales.

In 1937, while Jin Yong was a middle-school student in Jiaxing (a city prominently featured in Condor Heroes), the outbreak of the full-scale Japanese invasion of China forced the entire school to evacuate to the south, starting the author’s life in exile from the region of his birth.

In 1942, Jin Yong was accepted by the Central School of Governance in Chongqing, one of Republican China’s most prestigious institutions during the resistance against Japanese invasion and closely affiliated with the Nationalist Party (also, unlike other competing schools, it was free). On account of his excellent English, he studied in the Department of Diplomacy, earning top marks.

Throughout his years of schooling away from home, Jin Yong excelled academically, but he also showed a rebellious streak by penning stories satirizing school authorities, joining student movements, and speaking out against bullying Nationalist Party student operatives – not unlike many of the unruly heroes in his future novels who would stand up against injustice. As a result of these actions, he was expelled from high school and again, later, from the Central School of Governance.

In 1948, Jin Yong graduated from the law school of Soochow University in Shanghai. Thereafter, he joined Ta Kung Pao, one of China’s oldest newspapers, and worked as a reporter, translator, and editor in the Hong Kong bureau. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, Jin Yong tried to join the diplomatic corps of the new government in Beijing, but the effort came to naught (likely as a result of disagreements with Beijing’s foreign policy), and he settled in Cantonese-speaking Hong Kong. There, in the early 1950s, he became an active film critic and wrote scripts for the colony’s booming film industry.

In 1955, Jin Yong’s career shifted dramatically when he wrote The Book and the Sword, his first wuxia novel. Serialized in the New Evening Post, the story was an instant hit. Over time, his literary voice would grow more confident and mature, but the combination of traditional wuxia tropes with modern cinematic pacing and vivid characterization, already evident in this first effort, would become a persistent mark of his books.

In 1957, he began to serialize Legends of the Condor Heroes in Hong Kong Commercial Daily. Often considered the work that cemented Jin Yong’s place in the literary canon of modern Chinese and world literature, Condor Heroes is an epic work that synthesizes the influences of multiple literary traditions, both Chinese and Western, as well as techniques from the toolkit of a screenwriter. The novel features a sprawling plot and numerous memorable characters, and builds a layered, complicated jianghu – a universe of rival schools of martial artists following as well as challenging the ideals of traditional xiake, that is, heroes outside the corrupting sphere of official and state power. Jin Yong would add to and refine the world of jianghu over successive works, raising the moral stakes and elaborating upon the nuances.

Later in 1957, he resigned from Ta Kung Pao due to his opposition to the ‘Great Leap Forward’ movement in the People’s Republic. The serialization of Condor Heroes was completed in 1959.

Also in 1959, Jin Yong and his friend Shen Pao Sing founded Ming Pao, the newspaper where most of his later novels would be serialized. Ming Pao struck a distinctive political stance (for instance, calling for support for the refugees fleeing into Hong Kong from the mainland, in defiance of the Hong Kong government’s policy of capture and deportation) and gradually developed into a publishing empire that offered a haven for Chinese literature in Hong Kong during the turbulent decades of the Cold War.

Between 1955 and 1972, Jin Yong published fifteen pieces of wuxia fiction of various lengths, and it is on this corpus that much of his literary reputation rests. However, in contrast to Jin Yong’s present popularity across the Chinese-speaking world, most Chinese readers at the time could not enjoy these works at all (at least not legally) because Jin Yong earned the extraordinary distinction of being a writer reviled by governments on both sides of the Taiwan Strait. China banned the books due to a variety of political sins by Jin Yong, among them his criticisms of China’s nuclear weapons program and the Cultural Revolution (at one point, Jin Yong had to leave Hong Kong due to threats on his life from extremists). On the other hand, Taiwan, under the Nationalist government, banned the books for perceived satire of Chiang Kai-shek (see, for example, the ‘Eastern Heretic’ hiding on an island in the East China Sea) and sympathy for leaders of historical rebellions.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that Jin Yong’s books were finally available in China (Deng Xiaoping was one of his earliest fans), though these were unauthorized editions. And only in the 1990s could authorized editions of Jin Yong be purchased in China. In Taiwan, despite the ban, his books were available to a limited extent in underground editions, and the ban was finally lifted in 1980.

After he retired from writing wuxia, Jin Yong went on to have a distinguished career in Hong Kong publishing and politics. Though he was earlier hated by governments in Beijing as well as Taipei, the power of his literary creations – aided by the popularity of Hong Kong TV drama adaptations – made him into a figure courted by all sides. He visited both Taiwan and China, meeting with the paramount leaders of each. In 1982, during negotiations over the status of colonial Hong Kong, Margaret Thatcher met with Jin Yong, hoping to persuade him to support continued British control of the territory; Jin Yong turned her down.

In his later years, Jin Yong undertook at least two rounds of major revisions to his books, making thousands of changes to the text. These revisions, sometimes prompted by reader feedback, provide a fascinating glimpse into the author’s composition process (and can generate heated debates among passionate fans). This particular translation is based on the latest revised version of Condor Heroes, reflecting the final form of the text as Jin Yong wished it.

In 2010, Jin Yong received his Ph.D. from Cambridge University for a thesis titled ‘The imperial succession in Tang China, 618–762.’

On October 30, 2018, Jin Yong passed away at Hong Kong Sanatorium & Hospital. By then, he was a cultural icon with no parallel in the Chinese-speaking world. He held dozens of honorary professorships in universities in Hong Kong, China, and Taiwan, as well as abroad, and a long string of international honors followed his name. Generations had grown up reading his books and entire academic disciplines developed around their analysis. His fiction had achieved a most rare feat: popular with the broadest swath of the reading public and praised by highbrow literary critics. Everyone, from politicians to street vendors, would quote Guo Jing’s pronouncement, ‘A true hero is one who serves the people and country,’ and reference the ‘Nine Yin Manual’ in conversation, much the same way those of us in the United States would quote ‘With great power comes great responsibility’ or refer to the Sorting Hat of Hogwarts. His novels have inspired countless imitators and been adapted into movies, radio dramas, TV shows, comic books, video games, mobile games, and surely will continue to find new life in mediums yet to be invented.

When news of his passing became public, Jin daxia was mourned by readers around the world, and in Xiangyang, the city that Guo Jing defended from Mongol invasion in Condor Heroes (at least in earlier editions), residents lit candles all over the old city walls to bid him farewell.

Despite Jin Yong’s incredible popularity in the sinophone world, he isn’t well known to English readers. Indeed, Legends of the Condor Heroes had never been translated into English until Anna Holmwood undertook this present effort.

Various explanations have been offered for this puzzle. Perhaps Jin Yong’s works are too ‘Chinese,’ some suggest. Maybe the world of jianghu relies on a certain shared cultural sensibility and historical context, making it inaccessible to non-Chinese readers.

Jin Yong’s fictional world is certainly Chinese. It presumes a level of knowledge in the reader concerning Chinese geography, history, philosophy, literature, and even topolects to fully unlock its charm. Jin Yong’s prose is steeped in a beauty reminiscent of the baihua novels of the Ming dynasty, and he draws from Classical Chinese texts liberally to add depth and color. His books inculcate in many younger readers a reverence and appreciation for China’s classical heritage like the work of no other modern writer. Composed in the aftermath of wars that threatened to annihilate ‘China’ as a country and during a period when the very idea of a modern ‘Chinese’ identity was contested ground, Jin Yong’s novels seem to linger over definitions of patriotism, the limits and substance of what it means to be Chinese, and the conflict between individual choice and dogmatic, received morality. Could these themes transcend their time and place?

But this view ignores aspects of Jin Yong that make him eminently ‘translatable.’ Jin Yong’s own cosmopolitan background means that the novels are also permeated by influences from Western literature, drama, and cinema. As well, his heroes’ insistence on the primacy of individual conscience over ideological orthodoxy is a core value of our shared modernity. Moreover, the themes of his novels could just as easily be restated to be love of homeland (native as well as adopted), the fluidity and malleability of identity, the insistence on individual freedom against corrupt and oppressive institutions, and above all, the triumph of those who dare to love and trust over those who cling to hate and doubt.

I believe these are universal themes.

What is it like to read Jin Yong in translation?

Some readers demand that a translation evoke in the target readership the same responses the original evoked in the source readership. This, to me, is misguided. The ‘meaning’ of a literary work is a shared creation between the text and the reader, and why should readers with wildly divergent assumptions and interpretive frameworks extract the same experience from the same text – let alone a text and its translation?

The reader who first followed Condor Heroes in the pages of Hong Kong Commercial Daily did not have the same responses as the college student in Nationalist Taipei who devoured a banned copy under a blanket, illuminated by flashlight. The parent in Beijing who read a pirated copy of Condor Heroes during the earliest years of China’s ‘reform and opening-up’ years, in the literary desert left by the Cultural Revolution, had reactions vastly different from the child in LA who discovered Jin Yong decades later on her phone, between quick swipes in WeChat and sessions in Snapchat.

Jin Yong’s wuxia world, as it has been transmitted across the sinophone world down the years, has always-already translated itself in the eternal dance between text and reader, co-telling a timeless story with ever-changing audiences. Such is the fate of all true classics. It is long overdue to take the translation one step further, to go across languages.

No, reading an English translation is not like reading the Chinese original, nor should it be. When stepping across the gap between cultures, the translator must re-create a work of art in a new linguistic medium, with all the hard choices that journey entails. Holmwood’s translation must make explicit some things that are in the realm of the implicit for Chinese readers, and must leave some concepts opaque when they depend upon a lifetime of acculturation. It must deploy textual technologies to aid readers who do not share assumed context: introductions, dramatis personae, endnotes, and so on.

Yet, carried by the text’s smooth and fluent flow, the English reader grows used to unfamiliar names and colorful sobriquets, becomes acclimatized to novel patterns of conversation and unaccustomed metaphors, learns the history of a Song China that truly existed while getting lost in the fantasy of a jianghu that never was. The English rendition takes on its own lively rhythm, assemble its own self-consistent web of symbols, and builds a new aesthetic mirroring the original but welcoming a new audience.

Dear reader, you are about to enter an enchanting world unlike anywhere you’ve ever been, and to be introduced to heroes and villains that will stay with you for a lifetime, long after you’ve turned the last page.

Step into the jianghu, and may your journey be as thrilling as it is fruitful, and your heart be as stout as it is open.

–Ken Liu

Introduction © Ken Lui 2019 and illustrations from The Folio Society edition of Jin Yong’s A Hero Born, exclusively available from foliosociety.com